Dunes, Lighthouses and Shipwrecks

Jockey's Ridge State Park is a 414 acre park and is home to the largest sand dune on the East Coast, about 140 feet high. The trek to the top of the highest dune allows a spectacular view of both Nags Head and Kill Devil Hills, as well as the Roanoke Sound and the Atlantic Ocean on opposite sides of the narrow stretch of land. It is an example of a medano- a huge hill of shifting sand that lacks vegetation. There are serveral prominent sand dunes in the area, but Jockey's Ridge attracts visitors of all types-kite flyers, hang gliders, sand surfers, and nature lovers. We spent a good 2 hours walking the dunes and learning about the unique microclimate and the plants and animals that prosper in this harsh environment.

Jockey's Ridge State Park is a 414 acre park and is home to the largest sand dune on the East Coast, about 140 feet high. The trek to the top of the highest dune allows a spectacular view of both Nags Head and Kill Devil Hills, as well as the Roanoke Sound and the Atlantic Ocean on opposite sides of the narrow stretch of land. It is an example of a medano- a huge hill of shifting sand that lacks vegetation. There are serveral prominent sand dunes in the area, but Jockey's Ridge attracts visitors of all types-kite flyers, hang gliders, sand surfers, and nature lovers. We spent a good 2 hours walking the dunes and learning about the unique microclimate and the plants and animals that prosper in this harsh environment.It was 2:30 PM before we took our leave of the Park and realizing that we had about 30 miles to go before sunset, we needed to pedal hard down the rode. Within a few miles we left the housing developments behind and finally found the Outer Banks experience we had anticipated...grand vistas of ocean and sound unspoiled by development. Blessed with a tail wind, we rode strong and hard, covering 34 miles in less than 3 hours. It was bicycling at it's best.

About Cape Hatteras

Cape Hatteras National Seashore is at the ocean's edge, but no well-defined boundary marks where the sea ends and the land begins. It stretches north to south across three islands - Bodie, Hatteras, and Ocracoke. The islands are linked by State Highway 12 - a narrow, paved road - and Hatteras Inlet ferry. Some of the special natural and historical features that you can visit along the way are described briefly below. The highway also passes through eight villages that reflect the nearly 300-year-old history and culture of the Outer Banks. Here land and sea work together in an uneasy alliance. They share many valuable resources. But the sea fuels the barrier islands and there are few places that escape its influence. Dwarfed, odd-shaped trees often caught our eye. Severely pruned by salt-laden winds, these trees are just one example of how the sea affects living things. Closer to the sea, shore birds patrolling the beach for food are interesting to watch. Some catch small fish or crabs carried by waves, while others probe the sand or search under shells for clams, worms, and insects. There are also maritime forests where you leave the sea behind briefly. These woodlands of oak, cedar, and yaupon holly grow on the island's higher, broader, somewhat protected parts. In the protected waters west of the islands you can find excellent opportunities for crabbing and clamming. The ocean also harbors a bounty of life, which includes channel bass, pompano, sea trout, bluefish, and other sport fish. Wintering snow geese, Canada geese, ducks, and many other kinds of birds populate the islands. The best time for observing birdlife are during fall and spring migrations and in the winter. Salt marshes are a source of food for birds and other animals year-round. Here sound waters meet the marsh twice each day as tides come and go, exchanging and replenishing nutrients. At the ocean's edge, you are always on the threshold of a new experience.

The Graveyard of the Atlantic

Bright red holly berries and wildflowers offer a brush of color that enlivens the mostly green, brown, and blue landscape. It is a landscape that is unusually peaceful - but not always. Storms sometimes batter the islands with fierce winds and waves.

To many people, the Outer Banks are synonymous with shipwrecks. Indeed, one would have trouble finding a more representative or fascinating aspect of local history. Just as the sea has always been an integral part of life on these barrier islands, so too have been its many victims. A countless number of ill-fated vessels as well as many of the courageous seafarers who manned them have succumbed to the local "perils of the sea."

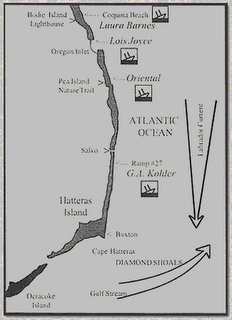

Why have so many ships been lost, after the lethal dangers of the "Graveyard of the Atlantic" became widely known? Unfortunately, avoiding these navigational hazards is much more difficult than recognizing them. In days gone by, it was the wooden sailing ship carrying goods and passengers that kept the nation's commerce afloat. To follow coastal trade routes, thousands of these vessels had to round not only North Carolina's barrier islands, which lie 30 miles off the mainland, but also the infamous Diamond Shoals, a treacherous, always-shifting series of shallow, underwater sandbars extending eight miles out from Cape Hatteras. While many believe that navigating Diamond Shoals is the only challenge, there are several other complicating factors.

First, there are two strong ocean currents that collide near Cape Hatteras. Flowing like massive rivers in the sea, the cold-water Labrador Current from the north and the warm Gulf Stream from the south, converge just offshore from the cape. To take advantage of these currents, vessels must draw close to the Outer Banks.

Ordinarily following this course would not lead to trouble, but the storms common to the region can make it a dangerous practice. Devastating hurricanes and dreaded nor'easters overwhelm ships with raging winds and heavy seas or drive them ashore to be battered apart by the pounding surf. Since the flat islands provide no natural landmarks, ships caught in storms often ran aground before spotting land and realizing their predicament.

Combined, these natural elements form a navigational nightmare that is feared as much as any in the world. Pirates, the American Civil War, and German U-boat assaults have added to the heavy toll nature has exacted. The grim total of vessels lost near Cape Hatteras is estimated at over 1000.

While hundreds of these "dead" ships now reside in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, their legacy lives on in many ways. Mariners stranded on the islands often chose to remain, establishing families and a heritage, which continues to this day. Many island residents made a substantial part of their living salvaging cargoes (a practice known as "wrecking") and dozens of local buildings were built entirely or in part from shipwreck timbers. Due to the frequent storms and many other navigational hazards resulting in great loss of vessels, the U.S. Lighthouse Service, U.S. Lifesaving Service (1874-1915), and U.S. Coast Guard (since 1915) have kept a steady watch for almost 200 years.

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is definitely the most famous lighthouse in the area. Authorized by Congress in 1794, it was first lit in 1803. At that time it was 90 ft. tall, made of sandstone, with a lamp powered by whale oil. The current lighthouse was designed in the 1870's and measures 210 feet tall. The height was needed to extend the roange of the light, which can be seen 12 miles out. The area around the lighthouse was constantly eroding, and after much study and debate, it was determined to move the structure in 1999. It took 23 days to moveit 2,900 feet where it now presently stands. During the summer months visitors can climb to the top to see the view. We weren't able to take advantage of that, but enjoyed it still the same.

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is definitely the most famous lighthouse in the area. Authorized by Congress in 1794, it was first lit in 1803. At that time it was 90 ft. tall, made of sandstone, with a lamp powered by whale oil. The current lighthouse was designed in the 1870's and measures 210 feet tall. The height was needed to extend the roange of the light, which can be seen 12 miles out. The area around the lighthouse was constantly eroding, and after much study and debate, it was determined to move the structure in 1999. It took 23 days to moveit 2,900 feet where it now presently stands. During the summer months visitors can climb to the top to see the view. We weren't able to take advantage of that, but enjoyed it still the same.The winds had picked up and we needed to set out towards the town of Hatteras to catch the ferry to Ocracoke Island. The headwind was strong and we pedalled hard, but it never seemed like we were making any ground. To get to our chosen campsite before sundown, we needed to catch the 3:30 ferry. It was a race against the clock, one of the few times we felt rushed on our trip. We made it with a scant 3 minutes to spare, and had a chance to catch our breath a relaxing passage across the Sound to Cedar Island and new adventures.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home