Crossing the Mason Dixon Line

Geologically, the river is extremely ancient, often regarded as the oldest or second oldest major system in the world. It is far older than the mountains through which it turns - the flow of the ancient Susquehanna was so strong that it was able to cut through the mountains even as they were forming from the collision of Africa and North America some 300 million years ago. Remarkably, the river's age means that it actually predates the Atlantic Ocean. What all this means to a bicyclists is that the river is wide, and has carved a deep gorge through the surrounding mountains. We climbed in and out of the river valley three times, and also had to negotiate more hills in the surrounding fertile plateaus. But the vistas were sweeping and grand, and served as a sweet reward for all our efforts.

Crossing the river we encounter our first Civil War site. During the 1863 Gettysburg campaign, the Union commander resolved that Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army would not cross the Susquehanna. Militia units were positioned to protect key bridges in Harrisburg and Wrightsville (along our route), as well as nearby fords. Confederate forces approached the river at several locations, but were recalled when Lee chose to concentrate his army to the west at Gettysburg. Just to be on the safe side, the Union forces burned the one mile long wooden covered bridge between Columbia and Wrightsville. It must have been quite a sight, and you can still see the remnants of the bridge pilings in the river.

It was in Wrightsville that we needed to give Olga some attention. The chain that connects the pilot to the stoker (known as the “timing chain”) had been ridden over 800 miles and had stretched to the point that it was beginning to slip. For those who don’t ride a bike, chains do stretch, causing performance issues with pedaling and shifting. Our hero of the day was Travis at the “Cycle Works” bike shop. He took us on as an emergency repair, dropping everything that he was doing to help us. He also gave us some great local knowledge of the route ahead, and let us browse the internet to find info about lodging in Maryland. Travis my man, you are truly a “Trail Angel”.

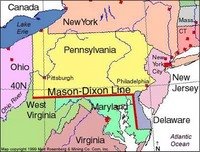

A day later, we rode into Maryland, “offically” crossing the Mason-Dixon line.

Although the Mason-Dixon Line is most commonly associated with the division between the northern and southern (free and slave, respectively) states during the 1800s and American Civil War-era, it was delineated in the mid-1700s to settle a property dispute. The two surveyors who mapped the line, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, will always be known for their famous boundary.

Although the Mason-Dixon Line is most commonly associated with the division between the northern and southern (free and slave, respectively) states during the 1800s and American Civil War-era, it was delineated in the mid-1700s to settle a property dispute. The two surveyors who mapped the line, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, will always be known for their famous boundary.It all began back in 1632. King Charles I of England gave the first Lord Baltimore, George Calvert, the colony of Maryland. Fifty years later, in 1682, King Charles II gave William Penn the territory to the north, which later became Pennsylvania. A year later, Charles II gave Penn land on the Delmarva Peninsula (the peninsula that includes the eastern portion of modern Maryland and all of Delaware). The description of the boundaries in the grants to Calvert and Penn did not match and there was a great deal of confusion as to where the boundary (supposedly along 40 degrees north) lay.

The Calvert and Penn families took the matter to the British court and England's chief justice declared in 1750 that the boundary between southern Pennsylvania and northern Maryland should lie 15 miles south of Philadelphia. A decade later, the two families agreed on the compromise and set out to have the new boundary surveyed. Unfortunately, colonial surveyors were no match for the difficult job and two experts from England had to be recruited.

Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon arrived in Philadelphia in November 1763. Mason was an astronomer who had worked at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich and Dixon was a renowned surveyor. The two had worked together as a team prior to their assignment to the colonies. After arriving in Philadelphia, their first task was to determine the exact absolute location of Philadelphia. From there, they began to survey the north-south line that divided the Delmarva Peninsula into the Calvert and Penn properties. They precisely established the point fifteen miles south of Philadelphia and since the beginning of their line was west of Philadelphia, they had to begin their measurement to the east of the beginning of their line. They erected a limestone benchmark at their point of origin.

Travel and surveying in the rugged "west" was difficult and slow going. The surveyors had to deal with many different hazards, one of the most dangerous to the men being the indigenous Native Americans living in the region. The duo did have Native American guides although once the survey team reached a point 36 miles east of the end point of the boundary, their guides told them not to travel any farther. Hostile residents kept the survey from reaching its end goal. Thus, on October 9, 1767, almost four years after they began their surveying, the 233 mile-long Mason-Dixon line had (almost) been completely surveyed.

Over fifty years later, the boundary between the two states came into the spotlight with the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The Compromise established a boundary between the slave states of the south and the free states of the north (however its separation of Maryland and Delaware is a bit confusing since Delaware was a slave state that stayed in the Union). This boundary became referred to as the Mason-Dixon line because it began in the east along the Mason-Dixon line and headed westward to the Ohio River and along the Ohio to its mouth at the Mississippi River and then west along 36 degrees 30 minutes North. The Mason-Dixon line was very symbolic in the minds of the people of our young nation struggling over slavery and the names of the two surveyors who created it will evermore be associated with that struggle and its geographic association.

The route had turned south again, and Washington DC was just two days worth of riding ahead. There really wasn’t anything standing in our way, except of course, we needed to find a few places to stay, and no services were listed anywhere on the map. It proved to be a very taxing two days.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home