Doin' the Charleston

The Swamp Fox

For those that grew up watching "The Wonderful World of Disney" on black and white

televisions, they're sure to recall the story of the man known as "The Swamp Fox". Francis Marion was an American revolutionary war hero, nicknamed the "Swamp Fox" by the British because of his elusive tactics. In 1761 he first distinguished himself as a lieutenant of militia by defeating some ambushed Cherokees. In 1775, Marion was elected to the South Carolina Provincial Congress as a representative. This Congress authorized the formation of two regiments, Marion was captain of the Second Regiment. In 1780 as a lieutenant colonel in the Continental service, Marion led an attack on Savannah. In May of 1780 Gen. Benjamin Lincoln surrendered Charleston to the British.In August 1780, Marion commanded guerrilla warfare against the Loyalists along the Peedee and Santee rivers. Marion chased away three Loyalist groups. Turning upon the British, Marion cut their supply lines, outran Sir Banister Tarleton's dragoons, raided Georgetown, retired to Snow's Island, and then again raided Georgetown.After the Continentals returned to South Carolina, Marion served as brigadier general of the militia under Gen. Nathaniel Greene. Aided by Continental troops, Marion finally seized Georgetown.

televisions, they're sure to recall the story of the man known as "The Swamp Fox". Francis Marion was an American revolutionary war hero, nicknamed the "Swamp Fox" by the British because of his elusive tactics. In 1761 he first distinguished himself as a lieutenant of militia by defeating some ambushed Cherokees. In 1775, Marion was elected to the South Carolina Provincial Congress as a representative. This Congress authorized the formation of two regiments, Marion was captain of the Second Regiment. In 1780 as a lieutenant colonel in the Continental service, Marion led an attack on Savannah. In May of 1780 Gen. Benjamin Lincoln surrendered Charleston to the British.In August 1780, Marion commanded guerrilla warfare against the Loyalists along the Peedee and Santee rivers. Marion chased away three Loyalist groups. Turning upon the British, Marion cut their supply lines, outran Sir Banister Tarleton's dragoons, raided Georgetown, retired to Snow's Island, and then again raided Georgetown.After the Continentals returned to South Carolina, Marion served as brigadier general of the militia under Gen. Nathaniel Greene. Aided by Continental troops, Marion finally seized Georgetown.At the battle of Eutaw Springs on September 8, 1781, he commanded the militias of North and South Carolina and drove the British back to Charleston.Marion was quiet and moody, yet humane and forgiving. He rose from private to brigadier general because of his intuitive grasp of strategy and tactics. Daring and elusive, he usually struck at night and then vanished into the swamps and morasses of the South. Many believe that the character portrayed by Mel Gibson in the movie "The Patriot" is based on Marion and his exploits.

Arriving on the outskirts of Charleston, the wind picked up and the rain became intense. We sought refuge at a local pizza parlor where they owner took pity and offered shelter from the storm, free coffee, as well as a good slice of NY style pizza. A new bridge links Charleston with nearby Mount Pleasant (complete with a wide bicycle/pedestrian walkway), but to get there, we needed to traverse some 10 miles of urban congestion. Maybe if the sun was shining it would have been fine, but the roadways were flooded and we got out the state highway map to devise plan B which took us on a rather circuitous but very safe route to the bridge. As we pedalled up the ramp entry, the sky finally cleared, and we coasted our way into Charleston and our nights lodging at the "Not So Hostel" hostel.

We chose the hostel because it would be inexpensive and located within walking distance to the downtown historic district. In hindsight, it was not one of the better decisions we've made. Located in a "transition" neighborhood, our room was tiny, the bed matress had more lumps than bad mash potatoes, and we had to share a bathroom with three others. That was somewhat to be expected, but as we discovered after the fact, we could have booked a hotel room two blocks away for $65 and spared ourselves the aggravation. So it goes.

A Bit about Charleston

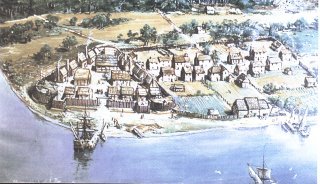

Much has been written about Charles Town, which was named in honor of King Charles II of England. King Charles was known for many things, but was most notorious for his womanizing and his lifestyle as a hedonistic pleasure seeker. His father was beheaded by the puritans for his exploits. It has been said the King Charles was "the father of his people, or at least, a great many of them." Founded in 1670 at Albemarle Point, early settlers were threatened by Spanish more than Indians, and Albemarle Point provided a vantage point from which to view any approaching vessels.

By 1690, Charles Town was America's fifth largest city. Initially, the population consisted mostly of English settlers, and later added many French Protestants called "Huguenots" as well as quite a few Irish.

Early Charles Town suffered a serious threat by murderous and thieving pirates, most notably Blackbeard. Blackbeard was apprehended and convicted in 1718 but quickly escaped. He was later captured and killed . Also threatened by Spaniards and Indians, it didn't take long for resentment to build against the English Lord Proprietors who were neither willing nor able to protect Charles Town from her attackers. Revolutionary activity began in Charles Town as early as 1719.

In spite of Charleston being referred to as "The Holy City", most likely because of the church steeples that distinguish the skyline, Charles Town was known more for its tolerance and decadence than religious fervor. In fact, the story line goes that there are 179 churches and over 200 bars in modern day Charleston, which seems like a good ratio to us.

Slavery was not a significant part of the first 30 years of Charleston history as she was mostly a trading town. By 1710, part of the very profitable trade and commerce in Charles Town involved the buying and selling of slaves which contributed significantly to early fortunes both from the trade of slaves and from planting using slaves.

Charles Town became one of the largest and wealthiest cities in America as the result of the trading of indigo, rice and slaves. African Slaves brought their knowledge of rice planting with them as well as the ability to survive the heat and disease. The same genes that made them prone to sickle cell anemia, made them resistant to malaria and yellow fever.

Charleston is known most for its charm and history; it's an experience that's difficult to convey. Charleston has a very unique story which there isn't time to tell here. The preseervation and restoration of the homes in the historic district is truly remarkable considering the history of the city. Charleston was devastated by several forces both natural and man-made, but probably nothing took more out of Charleston than the Civil War. With many buildings burned or severely damaged by the sustained artillery siege on Charleston, due to the economic destination that followed the Civil War, there was no money to tear down and rebuild. So Charleston remained in horrible condition for years, but with the original structures still intact. It is these structures that have been transformed into what is now known as one of America's most liveable and beautiful cities.

Trail Angel Marilyn

Good fortune smiled on us once again, as we had the pleasure of a great guide to the city. Our connection to Marilyn Durkee was through Mary Ellen's sister Donna. Mary Ellen had met Marilyn Durkee a few years ago when she was at a cooking school in France, but we were not prepared for her graciousness and hospitality during our stay. She drove us around the city, helping us take care of important chores, and was a fount of knowledge about the town and what it's like living in Charleston. She dedicated two days of her life to us, introducing us to her friends and city, and we were truly fortunate. Thanks Marilyn. You're an angel.

We were suprised at how vibrant the town seemed. There are three colleges located in Charleston, and the place was hoppin' with young folk. There were numerous restaurants to choose from (we did seafood and our first Carolina style barbeque), art galleries, museums...all the trappings of a live and thriving community. Our stay was short but fun filled. We were told that a cold front was coming in, and knew that we needed to continue our journey south. Leaving town by SR61, we rode passed three different historic plantations lined with some of the most spectacular live oak trees drapped with Spanish moss we had seen to date. Our destination for the evening was Givehans Ferry State Park, and we made it to the campsite with the last rays of sunlight in the western sky. The temperature was dropping, and we busily started to scout the area for firewood. It was going to be a cold, clear night, and a warming fire would be most welcomed.